Karen Bronze Drum |

|

|

Frog Drums and There Importance in Karen Culture Arts of Asia September/October 1983 issue ONE OF THE side effects of the Vietnam war has been the appearance of large numbers of beautifully cast bronze frog drums on the art markets of the world. Since most came from Laos, where many were purchased directly or indirectly from the Kha or Khamu people who inhabit the remote upland areas of the northern part of the country, they are often referred to as Kha or Laotian drums. There is now available quite a body of research which strongly suggests that some of these drums seen today were probably made in eastern Burma by Shan craftsmen for their primary customers, the Karen, a distinct minority people straddling the mountains which separate Burma and Thailand.

The Karen, numbering approximately two million on the Burmese side, with a further 200,000 in Thailand, include sub-groups such as the Skaw, the Pwo and Kayah. As with most hill tribes of Southeast Asia, their origins are obscure. Karen legends point to the upper reaches of the Huang Ho river in China as a possible centre of origin, from which they migrated south-ward via Yunnan into Burma around A.D. 600-700. They are traditional slash and burn agriculturalists and formerly lived a longhouse way of life. As animists, they believed in Nats, spirits that reside in rocks, trees, water and other objects. At times these spirits might prove dangerous, and to ensure that all went well, they had to be regularly propitiated with sacrifices, offerings and taboos. Throughout their little known and largely conjectural history, the Karens have always regarded the frog drum as their most precious possession, believing that ownership bestowed the triple boons of wealth, status and security on those fortunate enough to own one. Early British travellers to the present-day Shan states and Kayah and Kawthoolei states noted that the Karen tribes had a passion for the possession of frog drums or pazi,as they are called in Burma. O'Riley, the first English district officer to Toungoo in 1857 remarked, "they [the drums] were held in such high esteem, that in the more remote villages even children were bartered for them." The deep sonorous tone of the drum was considered pleasing to the presiding N at spirits of the mountains, and the resulting echoes signified their approval and hence guaranteed good fortune to the people. The drums were also used to summon the Karen ancestor spirits, to remind them to be on hand to witness important ceremonies such as marriage, house-warmings and funerals. At the same time the sound of the drums implored them to look kindly on their kin below and, when necessary in times of stress and misfortune, to use their good offices in securing favours from the Nat spirits to ease the burdens of those below. The Karen also believed that a spirit resided within the drum and at times it was thought beneficial to propitiate it with small bowls of liquor and rice. Failure to do so might result in the early death of the owner. Any changes to the surface of the drum were carefully noted. For example, condensation on the surface was not regarded as a good omen; it was interpreted as weeping and if nothing was done, sickness and death could result. To avert such a calamity, a ritual was performed with the blood of a chicken to appease the spirit of the drum. The Rev. Harry Marshall, a leading authority on the Karen people, has mentioned that some drums were regarded as auspicious and others inauspicious. He also talks of "hot" drums that were beaten at time of death and disaster, and "cool" ones used for festive occasions. Unfortunately there is nothing physically different to make a definite distinction between the two types of drums. Some of the more notable ones were given special names which when translated could have meanings such as "great resonance", "pure tone", etc.

The Karen used to store their treasures in frog drums and bury them secretly in the ground, believing that they could take their possessions with them after death. Until the sixteenth century it was the custom of the Shan, Karen and other tribes of eastern Burma at the death of a chief to bury his possessions, including his wives, elephants, weapons and other valued objects. The Karen, like other drum users in Yunnan and Vietnam, were known to bury their drums with their owners. Bayinnaung (1551-1581), one of Burma's greatest conquerors who in his heyday ruled over all of Burma (and a large part of Thailand) except for the Arakan coast, being a devout Buddhist forbade such funerary practices. As a compromise, token offerings were subsequently placed in graves. In place of a complete drum, a piece often in the form of a frog was cut off and buried. Hence some of the older frog drums may be incomplete or repaired.

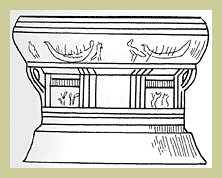

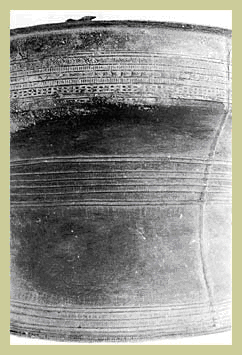

Drum base decoration The ownership of a drum also conferred status, for according to tradition, the owner of such an item stood higher in the community than if "he possessed seven elephants", the elephant being highly prized in Southeast Asia. Drums often formed part of the gift exchange preceding a marriage. They could be offered as compensation in disputes settled at the behest of the village elders.

Lacquered and gold leafed frog drums set in horizontal stands were important items of ritual in the Thai court, to be beaten when the king appeared, and they were used intermittently by Thai royalty even to this day. In a ceremony held on October 20th, 1982 when Queen Sirikit formally presented the Phra Buddha Nava Rajaboptr image to the city of Bangkok, frog drums formed part of the paraphernalia carried in procession. The Thai kings were known to give them to monasteries on occasions. King Rama IV, on his ascent to the throne, donated several frog drums to Wat Ba Wan and Wat Phra Keow. His successor Rama V, carrying on the tradition, gave two such drums to Wat Bencha. The ex-king of Laos is reported as formerly having from thirty to forty bronze drums in his possession.

Being primitive agriculturalists, the Karen were very dependent on the kindness of the elements for their welfare and livelihood. Consequently, it is not surprising to find that their highly prized drums also played an important part in agricultural rituals to secure abundant rainfall. So important was the agricultural cycle of activities that the Karen names for the months of the year reflect both the climate and the domestic and farming practices associated with the seasons. Led by a pair of warrior leaders, the Karen were also known to perform a line dance back and forth in two rows in a ritual to bring on rain. Drums were beaten for other farming rituals such as those at rice planting and harvest time. The valuable seed grain for the next year's crops was sometimes kept safely stored in the resonance case of a frog drum, which in addition to being impossible for rats to climb up, was thought to impart some magic power to enhance the efficacy of the germination process.

The Karen also believed that the bronze drums linked them to their remote past. Some associate the origin of the drums with Pu Maw Taw, considered to be one of their early ancestors. He was a diligent farmer who daily tended his steep hill rice fields located close to a cave. His efforts to harvest his grain were constantly being hampered by the depredations of a band of monkeys which continually stole his grain. In despair the old man wearily lay down and pretended to be dead. On finding him in a prone position, the monkeys clustered around him, remorsefully saying, we have eaten his grain, now he is dead. Let us perform a proper funeral for him." With that they carried his body to the mouth of the cave. Several monkeys then went to get their drums, which it appears they were in the habit of using for funeral rites. Of the three drums brought, one was of gold, another silver and the third white in appearance. As the monkeys were beating the drums, the patriarch sat up and began gazing around. This unexpected action caused the monkeys to flee in terror, leaving their drums behind. Pu Maw Taw took them and they became the most sacred possessions of the Karen people, who subsequently worshipped them in an annual ceremony. Unfortunately squabbles amongst the various Karen groups caused the drums to be stolen and lost to posterity. Despite the overwhelming importance of the drums in ritual and life, the Karen themselves, not being metalworkers, do not seem to have made them. According to Karen lore, the earliest drums were obtained from the Yu people, who could possibly have been the Jung or Yung people who occupied Yunnan in ancient times. Early Chinese sources have verified that bronze drums were used by the "Southern Barbarian" tribes of southwestern China as far back as the second century B.C. It is quite likely that they were in use in Yunnan when the ancestors of the Karen passed through there from western China into Burma.

Throughout the nineteenth century it is known that Karen bronze drums were cast by Shan craftsmen at Ngwedaung (Silver Muntain) some eight miles south of Loikaw, the capital of Kayah state. These craftsmen were also noted for making gongs, cow bells, silverware and jewellery. In addition to the various sub-groups of Karen, buyers from Laos, Thailand and Cambodia used to converge on Ngwedaung at the end of the rainy season in October-November to purchase drums to sell to various tribal groups such as the Tsa Khamu. They were bartered for elephants, silver, gold and other merchandise. It is reported that at one time U Sein of Loikaw even had a branch salesroom at The Burma House on Merchant Street in Rangoon to promote the export of frog drums. Because of the importance of the drums to the Karen, master craftsmen had to undergo certain purification rites before a drum could be cast at a time predetermined by astrological calculations. On the day before, they were required to undergo a cleansing ritual to invoke spiritual guidance during casting. After bathing, they made offerings of fruit and candles, then slept undisturbed that evening. When they arrived at the foundry the following morning, a circle was marked out in which the casting was to be performed. Within this area the wearing of footwear was prohibited. Swearing and the consumption of intoxicants were also forbidden until the work was completed.

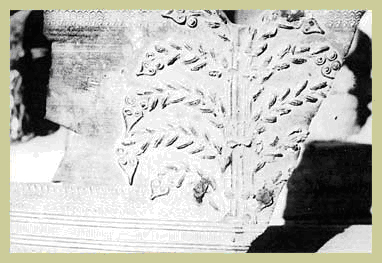

To begin the process and form the inside contour of the drum, a hollow clay core is built up from finely wedged red clay mixed with rice husks in the proportions of two parts of clay to one part rice husks. When sufficiently hardened, it is smoothed by turning on a lathe. It is then coated two to three times with a slip made from yellow clay mixed with finely strained powdered cow dung. After further shaping on a lathe, the form may be covered with a glue of boiled rice water which helps serve as an adhesive for the wax. A wax compound is made from a combination of approximately ten parts of indwe tree resin, seven parts of beeswax and four parts of crude oil. The thick brown wax is rolled out to a uniform thickness, cut into squares and bonded to the clay core with crude oil. The amount of wax used is carefully weighed so that the correct amount of molten metal can later be added. For decoration of the resonance case and tympanum, concentric circles characteristic of frog drums are made with a blunt chisel. Engraved motifs, such as birds and fish, are created with metal dies. Repetitive geometric patterns may be impressed on the surface with small rollers, while raised decoration, for instance the stylised tree that sometimes appears at the base of a drum, is created with strips of wax. Handles and three-dimensional figures, such as frogs and elephants, are made from moulds or modelled separately, then pressed on to the surface. Small sprues one to two inches long, which provide conduits for the molten metal and escape routes for the wax and gases, are set at various intervals over the surface of the drum. A slip of white clay mixed with rice husks is carefully applied over the whole wax surface, great care being taken to fill in all the tiniest crevices of the designs. A thick three to four inch layer of clay kneaded with either rice husks or horse dung is applied to form the outer mould. The inner and outer moulds are aligned with small iron rods. To harden the clay core and to remove the wax, the mould is fired in a kiln constructed of mud and bricks. The molten metal, usually consisting of a mixture of copper, lead, tin and zinc in varying quantities, is poured into the mould from a ceramic crucible. Once the metal has been poured in, the mould is completely covered with earth and allowed to cool slowly for several days. When cold, the mould is broken open to reveal the drum which is then cleaned and rubbed smooth. The sprues and any other rough projections are filed even with the surface. The colour of the drum depends on the alloys used in casting and ranges from black and reddish brown"to greenish turquoise. The value of a drum depends on the metal content, the tonal quality, the artistry of the design and its ritual efficacy.

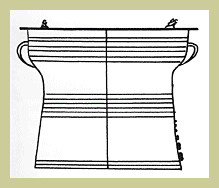

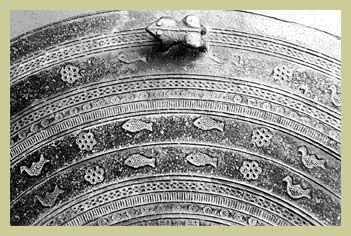

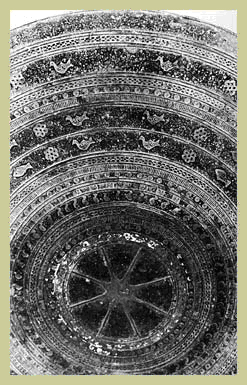

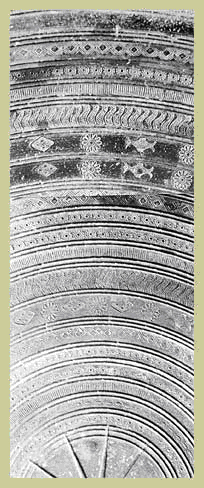

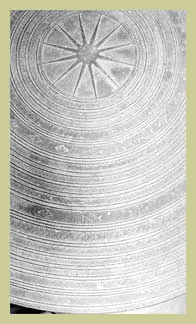

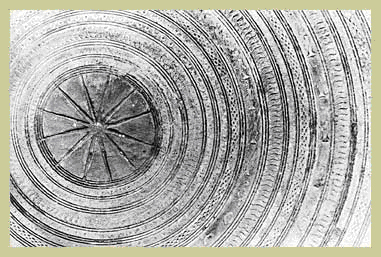

According to Dr Franz Heger's classification expounded in his pioneer study of bronze drums, Alte Metalltrommeln aus Südost-Asien (Leipzig, 1902), Karen drums have been classified as Type III drums. They exist in far greater number than any other drum types in Asia and have probably evolved from Type I examples. There is a considerable variation in size of the drums. The oldest Karen drums are generally smaller than the more recent examples, but as many new ones are now being made in small to miniature proportions, size is not a reliable indication of age. The overlapping tympanum varies from about nine to thirty inches in diameter and the resonance case is only slightly longer than the diameter of the tympanum. As with all bronze drums, a slightly raised star adorns the centre of the tympanum. This star has an even number rays for instance eight, ten, twelve, fourteen or sixteen, the points of which may be relatively short or thread-like in shape. On the one-frog drums the star usually has only eight rays, but there are exceptions to this. Between the rays of the star may be seen an engraved heart-shaped motif which resembles a resting butterfly with wings folded. On the earlier drums this may be quite large, while on later examples it decreases in size and may entirely disappear. Occasionally there are small rosettes and circles between the outer rays of the star, the tips of which may overlap into the first two to three narrow concentric rings surrounding the star. These slightly raised rings spread out in ever widening circles, dividing up the entire surface of the tympanum into bands for decoration. The number of rings between each band varies with the number of frogs superimposed on the tympanum. The smaller, earlier frog drums average about fourteen decorative bands separated by single rings, while the more recent three-frog drums usually have about nineteen bands separated by a series of triple concentric rings.

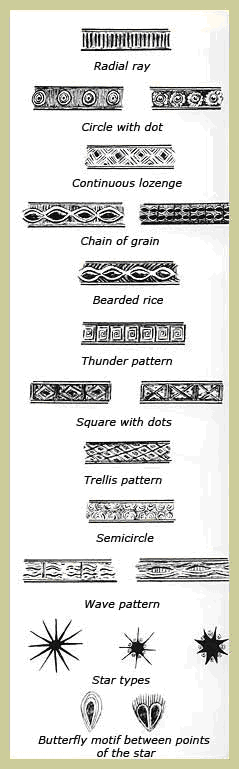

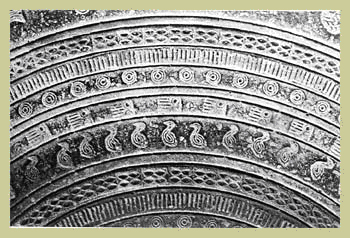

Decoration within these bands consists of both geometric designs and stylized representations of plants and animals. The first few bands closest to the star are incised with geometric motifs such as short, even, parallel lines or radial rays and circles with a dot, referred to by Heger as the "eye" motif On some later drums this becomes a continuous chain of rosettes which may be repeated in double bands. There arc various "rice grain" patterns. One of the earliest resembles a row of melon seeds laid end to end and has come to be called the "chain of grain" motif. It may also be seen as a double layer of grain. On some drums this design has small filaments at the side and is then called "bearded rice". The continuous lozenge motif; consisting of a diamond shape surrounded by parallel lines, is another popular design seen on frog drums. A variation of Chinese thunder pattern is occasionally found. On some later drums there is a small square motif set wi th a diagonal cross surrounded with dots around the periphery. Bands of semi-circular wave patterns and diagonal trellis and dot designs may also be depicted on the tympanum. Following the set of geometric motifs closest to the star there may be a single band of small stylised birds commonly referred to as ducks, which on the earliest drums are depicted as round and plump in a standing position. On later drums they change into a tear-drop shape and appear to be floating. Eventually this evolves into a highly stylised form with only the head and neck in a stretching position depicted, so close together that at first glance it takes on the appearance of a curved geometric pattern. These birds have been called ducks because this bird is very important in Karen folklore and was thought to ferry the souls of the deceased to the nether world. On the earlier drums this duck motif is usually immediately followed by a flag-like design that has been called an "owl" by Dr Cooler, the foremost authority on Karen drums. It consis ts of a small rectangle with one and a half to two circles or eyes located at one end, parallel lines and V-shaped lines filling up the remainder of the rectangle. This motif may be found in pairs on some drums; it disappears on the later ones and the space is filled up with other decoration.

A further interval of varied geometric decoration is followed by a fairly prominent band consisting of one or two rows of fish and large birds separated by rosettes. On the earlier drums these rosettes are quite wheel-like. They have also been called lotuses. The fish and birds may be single or depicted in pairs. On the earliest Karen drums the birds are archaic, wi h some resemblance to those seen on Type I drums and may be sitting, standing or floating. This band may be repeated on the tympanum of some drums. On many of the later drums the birds have taken a flying posture and the fish have disappeared, to be replaced by single lozenge motifs which alternate with the rosettes. This band may be repeated up to three times on the tympanum and in some cases may fill in for the "owl" motif. Further band's of geometric decoration usually adorn the outer bands of the tympanum. The final band is generally left blank, although on some of the later drums there are a few widely spaced rosettes in this area. The perimeter is usually bounded by a thin strip of braided decoration.

The design motifs on the tympanum are not always clear because of natural wear and tear and also the failure to fill up adequately all the finely incised lines of the mould at time of casting. The surfaces of some drums are quite pock-marked, probably because the mould was too hot at the time of casting. On some of the newer drums slightly raised sprue marks are noticeable on the surface of the drum, particularly in the area between the points of the star, for in many cases they have not been filed level with the surface of the drum. In some cases attempts have been made to disguise the sprues at the time of casting by placing them on rosettes.

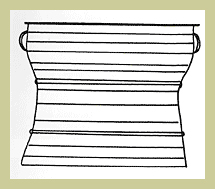

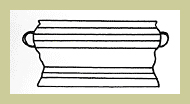

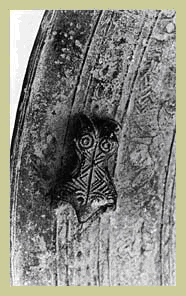

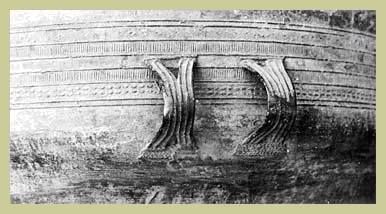

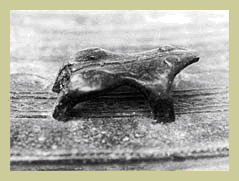

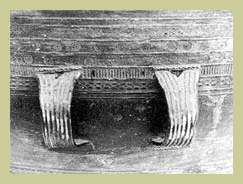

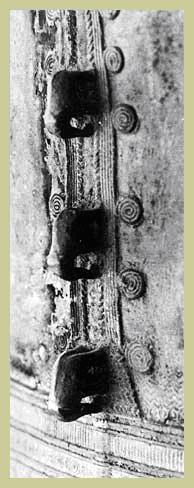

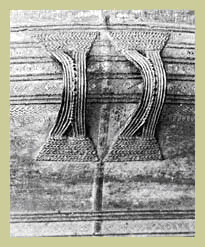

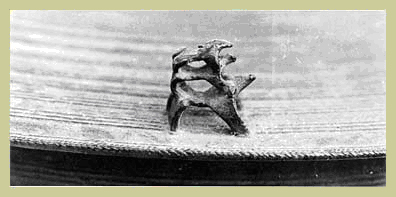

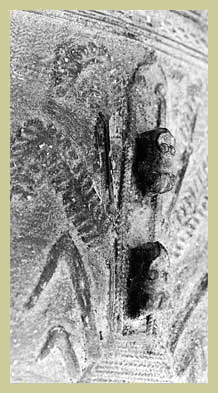

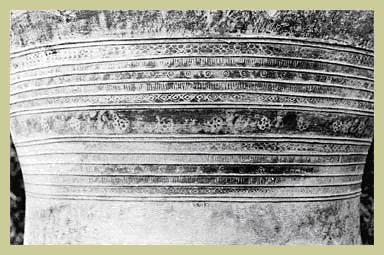

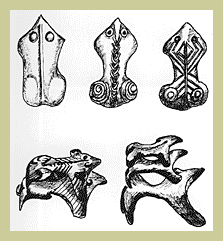

Frogs appear at each of the four ninety-degree angles around the perimeter of the tympanum. Like most of the animal motifs depicted on frog drums, they face an ti-clockwise and appear to be following each other. They are usually placed astride the last set of concentric circles with the left feet in the last geometric band and the right in the blank band. On the two- and three-frog drums the frogs are superimposed one upon the other, each successive one becoming smaller. The quality of the modelling varies greatly. As a rule the single frogs are much more finely wrought than the superimposed examples. They may be quite plain with protruding eyes, pointed nose, narrow waist and spreading haunches. The backbone is usually slightly raised, resembling a plaited line on some, while on others lines may radiate out from the backbone like ribs. There may be spirals on the haunches. On some drums the frogs appear to be different or much newer than the tympanum, as indeed they may be, for protruding above the general level of the drum, they were liable to damage. As previously mentioned, in some cases a frog might have been removed for burial with the deceased owner. The new owner would then replace the missing frog with a new one. The cylinder or resonance case with its slightly bulging upper portion has two or occasionally four vertical seams which are purely decorative in function. They are probably a vestigial feature copied from Type I drums which, unlike the Karen drum, were not always cast as a single piece, hence seams were necessary to join the drum together. Two pairs of angular handles, usually with triangular holes at the tops and bottom, are placed midway between the two seams on the nether portion of the bulge at the top of the resonance case. The handles are marked with vertical lines and occasional diamond shapes. The handles appear to be fastened to the resonance case by a series of plaited and zigzag lines. The handles serve not only as a device for ease in moving the drum, but provide the means by which it was suspended by a rope for playing with a cloth-padded bamboo stick. The drum was allowed to swing freely a few inches above the ground. The player steadied it while playing by hooking his toes into the handle close to the ground. Four to five bands of decoration adorn the bulge of the resonance case. The circle and dot, radial rays and continuous lozenges are the most common motifs here. The mid portion may also have seven to eight bands of decoration often separated into two parts by a wider band in the centre which may be left blank or may occasionally contain rosettes. Two to four lines of geometric decoration sometimes surround the base of the drum. Zones of decoration on the resonance case usually end in a band of lightly impressed, closely set wavy patterns, which on some may be in the form of a zigzag. The inner side of the resonance case is undecorated. Scrape marks made in the process of improving the tone of the drum are sometimes visible inside.

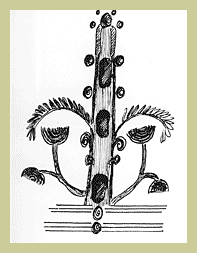

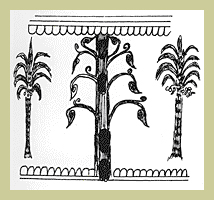

One of the most unusual features of the Karen drum, particularly those of slightly later date, is the placing of two-dimensional plant forms and three-dimensional animals usually towards the base of the resonance case, often aligned under a pair of handles. The most popular three-dimensional motif consists of a procession of two or three elephants in single file, as if walking down towards the end of the drum. The elephants are usually depicted in conjunction with snail shells which may be placed on either side of, or behind, each elephant. This design may be enclosed within a tree-like form so that the elephants seem to be walking down the trunk. The number of elephants is usually the same as the number of superimposed frogs on the tympanum. Some drums may be particularly elaborate, showing other flora and fauna in addition to elephants and trees. Newer drums may have a menagerie of fauna in the form of squirrels, fish, reptiles, insects etc. (See Roxanna M. Brown, "Bronze Drums of Laos", in ARTS OF ASIA, January-February 1975, the illustration on page 53.) On a few drums the decoration may be purely vegetal in the form of a tree or a sheaf of rice.

Using the internal comparative analysis method developed by Philippe Stern and Jean Boisselier in establishing a chronology for Southeast Asian sculpture, Dr Richard Cooler, in a doctoral dissertation on Karen drums for Cornell University, has attempted to trace, through a study of over four hundred drums, the evolution of Karen drums from their Type I prototype. He has taken what he considers to be key motifs on Karen drums - the large and small birds, fish, owl and single lozenge-and has carefully charted their various permutations through a series of seven evolutionary stages. The present writer is indebted to Dr Cooler's research which has greatly helped her to describe the general motifs and to prepare the accompanying diagrams. Dr Cooler's research, however, suffers from the problem that at present there are no known dateable examples of Karen drums to provide a chronological framework on which to hang his most interesting theories. Although Karen drums have probably been in existence for as long as a thousand years, there are no early historical records describing their appearance, since the Karen were not literate until the advent of a missionary-devised script in the late nineteenth century. Being a gentle, shy people, the Karen throughout their history have tended to withdraw in the face of contact with other races. Until the nineteenth century there have not been any detailed descriptions of Karen drums from Chinese or other sources. From previously quoted Burmese inscriptions we do know of their existence since Pagan times (eleventh to late thirteenth centuries). According to the Rev. Harry Marshall, none of the drums now seen can be thought with any certainty to date further back than two centuries. Dr Cooler in his dissertation also advances one possible explanation for the motifs which appear on Karen frog drums. He bases his theory on a Karen poem. He likens the tympanum of the drum to a magic pond which expresses the Karen ideal of prosperity. The star perhaps represents a splash with ripples in the form of concentric circles radiating out from the centre to embrace the various elements of an aquatic environment -birds, fish and perhaps turtles in the form of a lozenge. He claims that the "owl" motif disappears from the Karen drum at a particular stage of evolution because it does not fit in with the aquatic environment. Frogs, as amphibians, are depicted close to the perimeter of the tympanum with feet astride in the water and on the bank where they usually spawn. An elephant is not only a status symbol for its owner, but a beast of burden which can earn him a tidy sum by drawing logs. Snails, considered edible by the Karen, have featured in folklore describing the migration of the Karen people. It is hoped that the fruits of Dr Cooler's research will eventually be published in order to increase our knowledge and understanding of Karen drums, for few who have seen them have failed to be fascinated by their unusual shape and unique motifs. With the end of the Vietnam war and the subsequent closure of Laos to foreign contact, the export of drums from that area has largely ceased. Although there is still a trickle of genuine drums from Burma, there are not enough to meet the demand, and prices have soared. From a mere US$50-I00 in Vietnam war days, a good drum in Bangkok will cost US$IOOO-1500 today. A number of concerns in Rangoon and Mandalay in Burma and Thonburi and Chiang Mai in Thailand have been making reproductions to meet the burgeoning demand. During a recent visit to Burma the present writer had the opportunity to visit Hla Aung's bronze casting establishment in Tanpawaddy Mandalay and managed to see part of the casting process using the timehallowed methods already described. They only make drums to order, usually for foreign customers and sometimes for the Karen who still likes to use the drum for Karen New Year festivities held annually in midJanuary. Five to six are made at a time. A drum with a twenty-six inch wide tympanum takes about three months to complete. To age the drum a mixture of sulphur, kerosene and engine oil is applied to the surface. Heat may also be applied. Because of the amount of labour and the price of the metal, a new drum costs about US$250 in Burma. This firm makes no pretence that the drums it produces are anything but reproductions. Unfortunately there are a few establishments in Rangoon and Bangkok that are less scrupulous and are known to be passing off newly made drums as the genuine article. To determine whether a drum is old or not, a good test is to try lifting it. If it is fairly easy to lift, the chances are that it could be an old one. Many new ones are very heavy and weigh up to from fifty to seventy pounds. This is because the new drums generally have a very high lead content in the alloy which lowers the melting point for the metal and allows it to flow more easily into the mould with fewer mishaps. Such a drum does not have a very good tone when struck. A real drum, if intact, will have a most pleasing reverberating tone. The walls of the new drums are usually thicker, whereas on the genuine ones the walls are never more than one eighth of an inch thick. A check on the motifs will also help to identify whether a drum is new or not. A drum with a surfeit of archaic-type decoration combined with three-dimensional elephants and other fauna on the resonance case is most likely to be a reproduction, for the resonance cases of very early drums are devoid of threedimensional decoration. A few lighter drums have recently begun making their appearance on the market. Instead of being cast, they have been made from copper alloy sheeting. A careful look inside the resonance case should reveal that the tympanum and resonance case have been soldered together. These drums are not very sturdy and have been known to bend and buckle easily. The tone is light and there is not much ring to it.

A prospective buyer must also look to see whether a drum has been extensively repaired or not, for the price should vary accordingly. On some the tympanum and resonance case are from different drums. A careful check on the style of motifs on each section will reveal any discrepancies, while a look inside may show welding. Extensive rough patches on the resonance case are also an indication that a drum has been repaired. This may be further checked by looking inside the resonance case for metal of a different colour and thickness. The continuity or lack of it in the geometric designs will also alert one to repairs. While present-day owners of frog drums may not be aware that their bronze ornament or side table may have been the cause of tribal warfare or an important instrument in the ritual of Karen life, they should rejoice in the knowledge that as the owners of such a cherished object, they "are considered as standing higher in the community than if they possessed seven elephants. "

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||